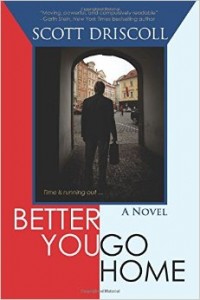

In January I met Scott Driscoll, a Seattle author and creative writing teacher. I welcomed the opportunity to talk with him because of our common interest in the Soviet bloc countries. Scott has written a novel set mainly in the Czech Republic, titled Better You Go Home. I read the novel eagerly last month. It is powerful.

Better You Go Home tells the story of a Seattle attorney, Chico Lenoch, visiting the Czech Republic a few years after the fall of the Iron Curtain. The Czech Republic is the homeland of Chico’s father, and Chico has become aware that he has a half-sister here. He looks for the woman partly out of desperation: Chico, a diabetic, is in kidney failure, and perhaps this sister could be the genetically matched kidney donor that he needs. Yet as he searches for both this woman and the truth about what happened in his family, he unearths the pain that his family endured . . . and inflicted. More and more, Chico’s quest goes beyond his own immediate medical need and becomes a drive to do the right thing for the sister who was left behind.

The book is sharply written in a close first-person narration, and the reader feels Chico’s diabetic weakness and dread as he walks this darkening path of generations-old hostilities. The novel is driven by the tensions of family secrets (based in similar events from Scott’s own family history), political corruption and medical emergency. This book is not light entertainment. The chain of cause and effect is complicated, and the characters are not always easy to interpret. But as I told Scott in an email to him after I finished the book, the complicated characters seem very real. Even the ones that appear most reprehensible have at times done helpful deeds, and the sympathetic characters have had their moments of caving in to despair or compromise. This conveys the stresses of people who have lived under Nazism and then communism. In my readings on Hungary, I have encountered similar stories of moral ambiguity. Sometimes we have to ask not only whether the characters (whether real or fictional) did right but also whether they felt they had any choice.

Scott’s comments about the writing of this book were illuminating. “It was family matters that encouraged me to set out to write this story to begin with,” he said. “What I especially wanted to know was what people thrust into a pressure cooker of politics, history, and geography (that was central Europe and the Eastern Bloc countries) did to keep their humanity alive. What I discovered was that there was no easy way to judge either side. There were consequences for my family. But I didn’t write this for them. I wrote this for my generation, the generation whose parents suffered the worst of these events. The generation whose upbringing bore the weight of unresolved conflict among parents, many of whom were forced emigres.”

Better You Go Home is a deep and beautifully written book. Read it. But don’t read it for escape. This is a novel you have to think about—and that’s a compliment.

Here is the Amazon link for the book